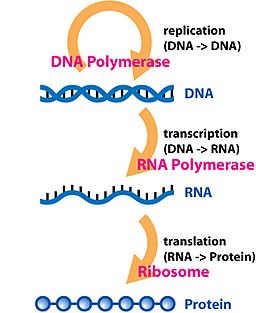

We covered a study on RNA and population genetics previously, but left with a question. What if RNA sequencing was used to study both genetics and molecular physiology? As an intermediate between DNA and proteins, it carries genetic variation in the DNA that codes for genes, while the abundance of the different messenger RNA transcripts tell us what genes might be important for a physiological response under some condition. RNA sequencing as a technology is up to the task, as well, while there are numerous bioinformatic tools available. Since biology and technology aren’t limits, why not investigate genetics and physiology in tandem with RNA sequencing?

Our study

That was our study. We based it on a couple other datasets to validate our findings. The primary one was previously run by by supervisor at the time, Ken Jeffries, who had done RNA sequencing work on the Sacramento splittail. They are under decline but not listed as endangered. Water issues in their native range in California’s San Francisco Bay are incredibly contentious, though, and climate change means that those issues won’t be getting easier to manage. One way that water affects the splittail’s population is through how salty it is- less water being released into the Bay means that their environment is getting saltier. So as part of his work, Ken led an experiment with wild individuals from two populations of Sacramento splittail exposed to elevated salinity: one less tolerant of salinity (a Central Valley population), and one more tolerant of it (a San Pablo Estuary population). He did RNA sequencing on samples from control, 3-day salinity exposure, and 7-day salinity exposure groups, and wrote a nice paper on the results.

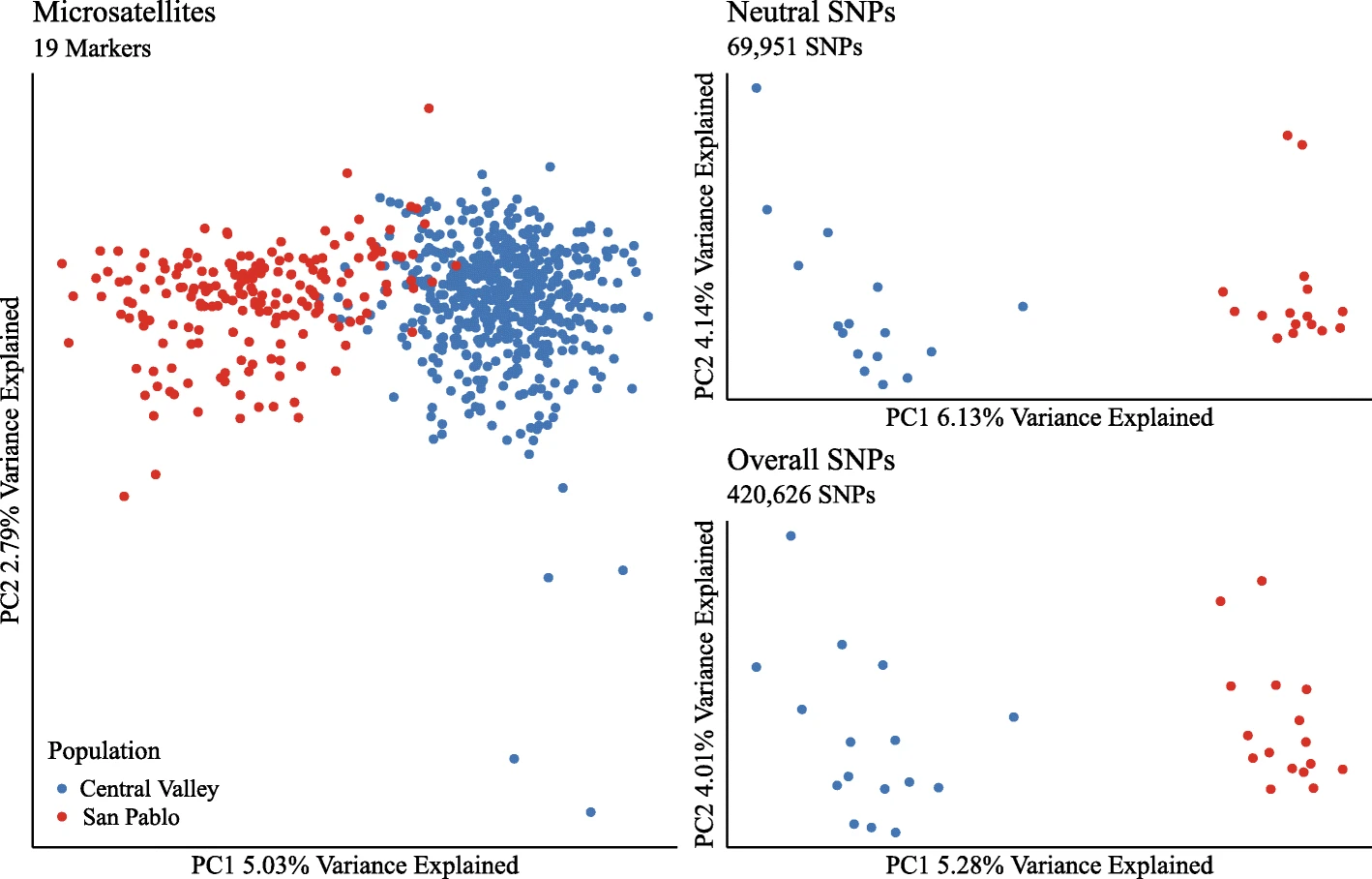

We knew that the two populations of splittail were different because of prior genetic work with microsatellites. So any genetic findings we made would need to be consistent with those other results before we believed them. The cool thing about RNA sequencing, though, is that it gives us specific nucleotide differences within genes- something microsatellites can’t really do. Given how different the two populations were at tolerating salinity, we thought that we could identify the genetic variation in genes that drove differences in their salinity responses. In addition, Melinda Baerwald, one of the authors on the original microsatellite study, offered to share the microsatellite data they used. So not only could we look at genetic variation that might be important for these fish, but we could directly compare genetic microsatellite and RNA results to see how well (or not) RNA sequencing gives estimates of genetic variation and differentiation. Establishing whether the RNA sequencing gives us similar results as the well-validated DNA-based method would also lend some credibility toward novel RNA results, as well.

Genetic differentiation as measured with RNA sequencing was consistent with differentiation from DNA here. The flipped X-axes on the PCA are no big deal, it’s the variance explained and discreteness of the different groups that’s important here. While the populations used in the RNA-based PCAs do look more discrete, as in they’re not overlapping with each other, personally I don’t see that as a big deal either since there are so few samples in the SNP data than with microsatellites. If there were more individuals sequenced for RNA, which would cost a lot of money, then the groups might overlap more in the PCA. How about measures of genetic variation?

Strictly speaking, this table is pretty awful to look at. I apologize for making it. It’s worth a quick look, though, since the results are so clear. Population differentiation (pairwise FST) identified with microsatellites was actually higher than that identified with the RNA SNPs, which is a little unexpected given how discrete the RNA groups are in the PCA above. But I think it’s a sample size issue, as pairwise FST had more ‘information’ about each population to work on with the microsatellites. Heterozygosity and gene diversity (HO and HS) were a couple times lower for the RNA SNPs and the microsatellites, which is pretty interesting since those are key measures of genetic variation.

What do these results mean? In this system, RNA underestimates genetic variation and differentiation compared to DNA. It’s an intuitive result to me because genes need to do things, whereas DNA in between genes, such as the microsatellites used here, don’t ‘do’ things really. There’s a term for what this in-between DNA is: junk DNA. This stuff is often ‘neutral’ from a genetic standpoint because it’s free to build up mutations, but that’s a superficial explanation and there’s a lot more going on. Genes, meanwhile, are limited in the mutations they can build up because any given mutation is more likely to be harmful than beneficial in a gene, so they have negative selection against mutations building up. Since mutations can’t build up as much in splittail genes here, then the RNAseq results don’t look as different between populations than the microsatellite results. So RNAseq could still be used for surveys of genetic variation in wildlife, but someone looking at the data would need to remember that the values are likely lower for RNA than an equivalent DNA-based dataset.

Isn’t the fact that the genetic variation, the SNPs, that we get from RNAseq representing genetic variation in genes useful, though? In other words, those microsatellites are nice for being well-established markers of genetic variation in DNA, but the SNPs from RNAseq might tell us how different genes are between groups. And those differences in genes might drive phenotypic differences between groups, such as how the San Pablo splittail can tolerate salinity much better than the Central Valley ones. Absolutely, and that was what we did with walleye RNAseq in Lake Winnipeg in the first part of this 2 part series.

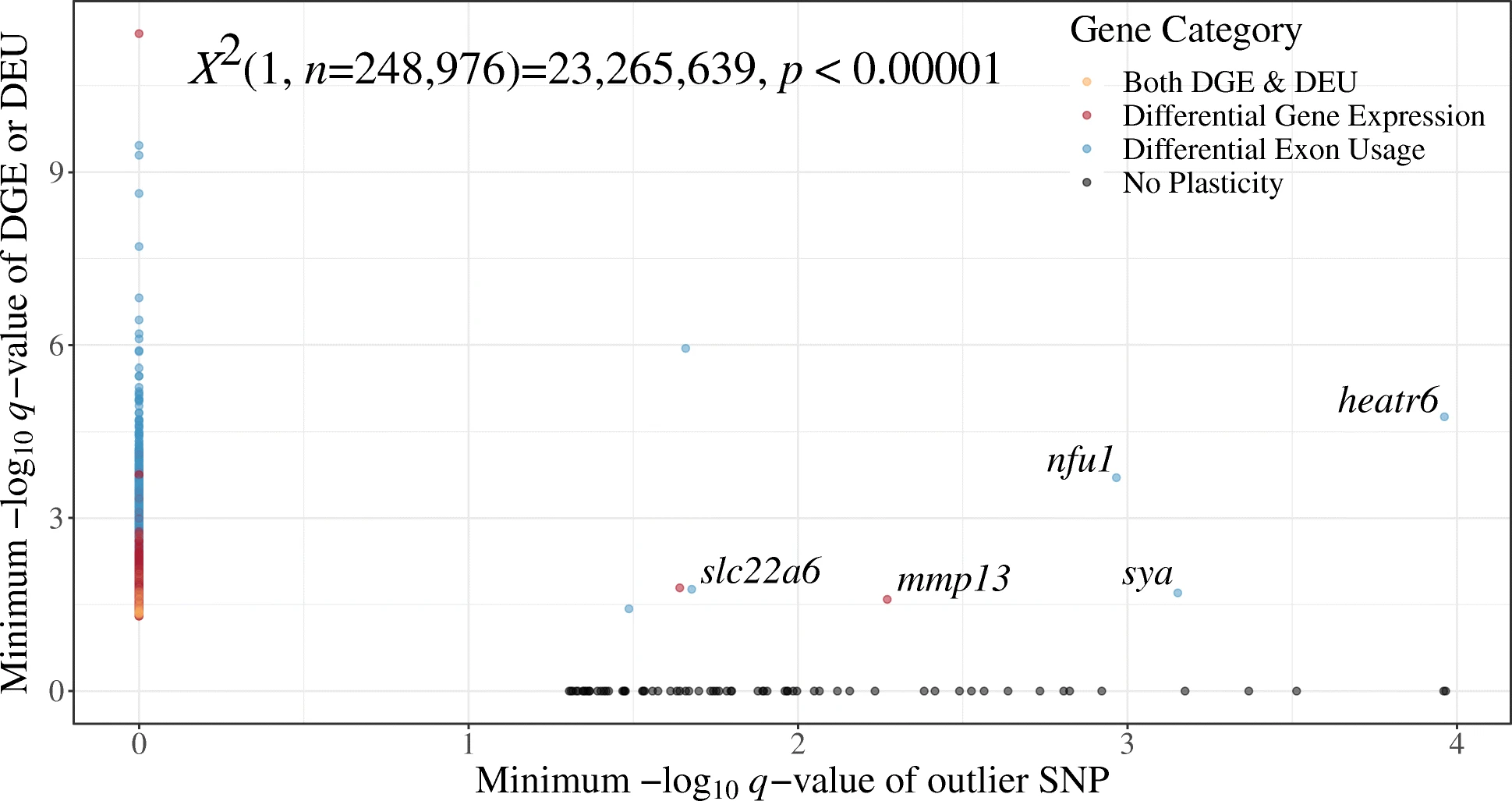

In this splittail paper, however, we took things maybe a step further. We wondered whether the genes that changed in their plasticity were also the ones that were genetically different between populations. Plasticity here refers to physiological ‘flexibility’, as in those genes were able to change how they were expressed somehow in response to salinity in Ken’s initial experiment. We first looked at differential gene expression, or differences in the abundance of the messenger RNA at different groups and timepoints. That was something Ken had analyzed in-depth with his initial paper. However, we also looked at alternative splicing, which I think of as a ‘building block’ approach to assembling a gene by splicing out bits of RNA (introns) and keeping other bits in (exons). By changing which bits are spliced out, the final protein can look different. The least common thing by far that we looked at was gene expression variability, although we found no significant results using that analysis (as cool as it is). Naïvely, I thought that the genes that had some kind of plasticity above would be the ones that were also genetically different between populations. I was incredibly wrong.

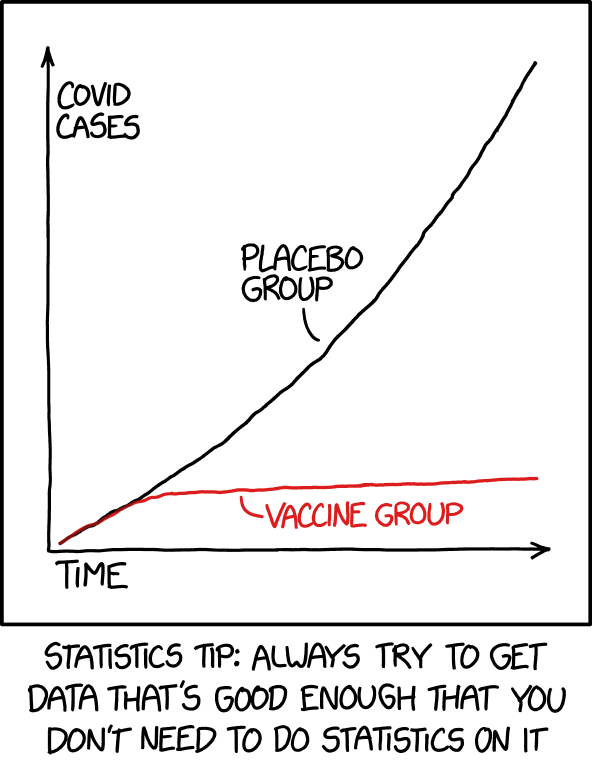

I was so wrong that the XKCD comic to the right seemed appropriate. Nevertheless, I did a chi-squared test of independence (results are in the X thing at the top of the figure) and the results are almost hilariously high. With 1 degree of freedom, a value of 3.841 seems like it would have crossed the threshold into ‘significance’, and the result here is 23.266 million. Biologically, this was pretty cool. It meant that the genes that were involved in a plastic response- changes in expression or splicing here, were not the ones different between splittail populations.

What’s up with that? Maybe what’s happening is that the genes that could change their plasticity somehow, whether by changing abundance of mRNA or how the proteins may look through splicing, did not need to undergo selective pressures to adapt to salinity differences. Genetic variation built up in those genes, but it might be neutral instead. There are some studies that found similar patterns to us, while others identified the opposite pattern- the genes that seemed to be under selection were also the ones that exhibited plasticity. Why the difference? We hypothesized that it may have to do with the environments the populations are adapted to- the splittail here used to live in environments of more stable and predictable salinity, until humans made things less predictable and often saltier. On the other hand, if something like the killifish evolved in wildly unstable environments, then maybe plasticity and selection happen in the same genes and genetic mechanisms.Who cares?

Who cares?

Anyone who is interested in using RNA sequencing in wild organisms might care. We showed that genetic surveys with RNA data do reflect general patterns seen with DNA, but to potentially lesser degrees. This could be helpful for ‘double dipping’ with data, so to speak, by getting one RNAseq data set that tells someone about both physiological and genetic differences among groups. Another group of people who may be interested are ones studying how evolution and phenotypic plasticity interact. Those are broad topics and this paper is a tiny contribution to that whole field, to be sure, but science is all about building up evidence.

If I were to do this study again, or had more time, I might apply something like iqtree to get a better idea of the evolution of genes in the RNA data. For instance, dN/dS might tell us about the ‘strength’ of selection in different genes and differentiate those that are mostly affected by neutral processes versus directional ones. Newer methods such as long-read RNA sequencing could make our inferences about splicing better than we could with this short-read RNA data. In any case, this paper was not earthshattering, but certainly advanced science in a few small ways and that’s a good thing.