Genetics used to be studied by looking at an organism’s phenotype, such as how peas looked, mutant fruit flies, or guinea pig coat colors. Richard Lewontin and John Hubby came up with the idea of running proteins through a gel to infer genetic variation- electrophoresis. Now though, genetic variation is practically only studied by looking at DNA, rather than proteins or external characteristics. Which is fine and useful. DNA is where that variation is ultimately stored, after all.

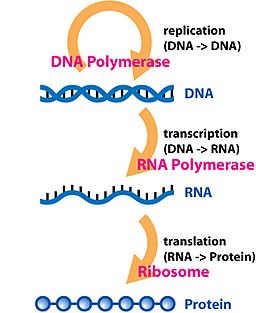

But there’s another piece in the DNA-to-phenotype pipeline I haven’t mentioned: RNA. It’s an intermediate, as DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is translated into a protein, in a process Francis Crick called the ‘central dogma‘. Strictly speaking, it’s wrong that information only flows in that direction, and RNA can do stuff too, so it’s not like proteins are the only endpoints of this process. I also tend to avoid thinking of concepts in terms of ‘dogmas‘ since science should be among the least dogmatic fields humans engage in. But broadly, for many genes, RNA has an important middle role between DNA and protein. What if we used it to study genetic variation?

This is a ridiculous idea, of course. There are advanced DNA sequencing methods that give up to 2.3 million base pair sequences in one go, or another sequencing method that yields hundreds of millions to billions of read copies from a single reaction lane. So it’s not like we’re limited by technology like Mendel, Morgan, and Wright were. But RNA sequencing is also possible and widely-used, to answer physiological questions such as what molecular mechanisms individuals used to respond to some stressor (shameless self-citation). Since RNA is transcribed from DNA, naturally the RNA will reflect the same sequence variation that DNA did. So in principle, RNA sequences tell us about genetic differences in similar ways to DNA sequence differences. And if someone was collecting RNA data anyway for a molecular physiology-based study, of course it could be used for genetics.

Our study

That’s our study. It’s on the walleye, a species consistently important for Canadian fisheries and called yellow pickerel in this table. Fish were caught from throughout Lake Winnipeg, and we non-lethally took gill samples in RNAlater for mRNA sequencing. The differential gene expression part of the study will be published soon, but I led the genetics side of the project.

The results are pretty straightforward, as far as genetics goes. Walleye are slightly different in a North-South gradient in the lake, which makes sense since the lake is kind of vertically laid out. Plus, the fish are known to move around a lot in other lakes and this one, so it’s not like fish from one part of Lake Winnipeg are isolated from another. We identified some differences across the lake nevertheless, and this is where RNA becomes pretty interesting- those differences could easily be tagged to particular genes. That’s because genetic differences in this case were measured with ‘single nucleotide polymorphisms’, or single base pair changes between individuals. These SNPs (pronounced ‘snips’) reside within the RNA transcripts we sequenced, and those transcripts can be linked (‘annotated’, in science-speak) to particular genes.

…Those genes let us look at what actual differences there might be between walleye of the north and south basins of Lake Winnipeg. For instance, people love their Manitoba greenbacks, walleye with a nice green colour that also tend to be nice and big. Perfect for fishing pictures. Those greenbacks haven’t been scientifically assessed, but they do seem to be from the southern part of the lake. And if there’s a genetic basis to their greenback-edness, then we might have caught the differences in those genes with RNA sequencing. More scientifically, the north and south parts of the lake are pretty different. The Red River in the south dumps a bunch of mud into the south basin, while the Dauphin River in the north takes relatively salty water from Lake Manitoba into the north basin. So if walleye hang out in one area versus the other more often, over time they might adapt to their environments to some extent. But again, the differences between fish in the two basins were small.

Interestingly, genes that seemed different between the two basins based on having multiple SNPs in their transcripts fell into a few categories. We expected signaling and expression regulation genes since regulation is one of the most regulated things by regulatory mechanisms in cells (regulators regulate regulators?). Cell membrane and cytoskeletal genes were certainly cool to see though, and potentially consistent with those environmental differences between basins in the lake. We spent some time writing about Claudin-10, for example, because mRNA abundance was associated with salinity in medaka. Could it be important in walleye? Maybe. But unfortunately, we did not have the resources to actually look at the protein made by the Claudin-10 or cell adhesion differences that might have been caused by that genetic variation.

The methods are extensive, but most of them are there to cover our genetic bases since we’re using unusual data. For instance, we used Colony to look for siblings in the data like in another paper I wrote, to address potential sibling structure in our samples. Luckily there were no siblings among our walleye. Another filter was for SNPs in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium for the population structure-based analyses (not the signatures of selection in genes described above). If I did the paper again, the Hardy Weinberg filter might be the first thing I remove since SNPs out of that equilibrium aren’t inherently uninformative. In addition, if I had another go at the project I might apply something like the HDplot program to address potential paralogy, and think about some kind of downsampling or normalization approach to address ways that read depth across individuals and transcripts within individuals may bias SNP calling and results. The conclusions about subtle differences in walleye across the lake aren’t wrong, though, since a follow-up study we did with DNA and more samples confirmed the initial results.

Who cares?

Fisheries and Oceans Canada researchers care, for one. They funded the study, and prior to our transcriptomic work here, the only other genetic study on Lake Winnipeg walleye had used more limited microsatellites. Not that it was their fault, it’s just microsatellites were the technology available at the time. This was the first genomic survey of walleye in the lake, although coauthors and I did a DNA-based one with more individuals later in my PhD. By confirming that Lake Winnipeg walleye are mostly the same across the lake, but establishing subtle differences between basins, managers have more context in which to make decisions about the fishery.

Anyone who wants to double dip with their data might care, as well. I referred to RNAseq being useful for molecular physiology above, and that’s still true. So if someone wanted to study molecular physiology and genetics? Well, RNAseq could be useful. In fact, it’s practically screaming to give us integrative genetic+physiological results when samples are taken in an appropriate way, something I’ll cover in a future week.

Of course, RNAseq for a certain number of individuals is more expensive than DNA sequencing. How much more expensive depends on the number of samples and how many reads you need. Generally, higher depth (more sequencing reads, as I use the term) means that someone is more likely to identify rare RNA transcripts in a dataset, and have more robust differential gene expression results. However, population genetics requires much higher sample sizes than does RNA sequencing. So the molecular physiologist is incentivized to get fewer individuals and more data per individual (e.g., 6-10 individuals per group with 50 million+ reads each), while the geneticist is incentivized to get more individuals and does not need as much data to call SNPs (e.g., 20-30+ individuals per group, with many times fewer reads necessary per individual). For similar reasons, many RNAseq studies take their individuals from one population, which I loosely mean as a genetically distinguishable group of individuals. The scientific value of results from looking at the genetics of one population is more limited than otherwise, since many population genetic tests involve contrasting groups. Other RNAseq-based studies study captively bred individuals, whose parents were sampled from the wild. The data from the offspring of wild parents is filled with complex issues introduced by family structure, and there’d be all sorts of issues with trying to generalize those results to the wild population.

Why did our study work? Because randomly sampled wild large walleye from 3 sites in Lake Winnipeg, over two years, with 8 fish chosen for RNA sequencing per year per site. That’s 8 x 3 x 2 = 48 fish, which is not great but not terrible for genetics. From the one RNAseq dataset, we got to look at both how different the fish are in different parts of the lake (this study) and how they are responding to their environment (soon to be published!).

If a researcher is thinking about assessing the genetics of individuals across an environment, then it’s possible that using RNAseq to also get that physiological information is a good idea. Alternatively, someone could be considering a survey of the physiological responses of individuals across an environment. That second person would have the much cheaper, but limited to few genes qPCR to assess mRNA transcript abundance, or RNAseq. If they chose (and had the budget for) RNAseq, they could consider whether the sampling strategy works for genetics, as well. One thing unmentioned in this post are specifics of getting molecular physiology results from the data, and practical ways to combine the genetic and physiological results. That will have to be covered in part 2…

Pingback: Double Duty for RNA: Part 2 | Dr. Matt Thorstensen